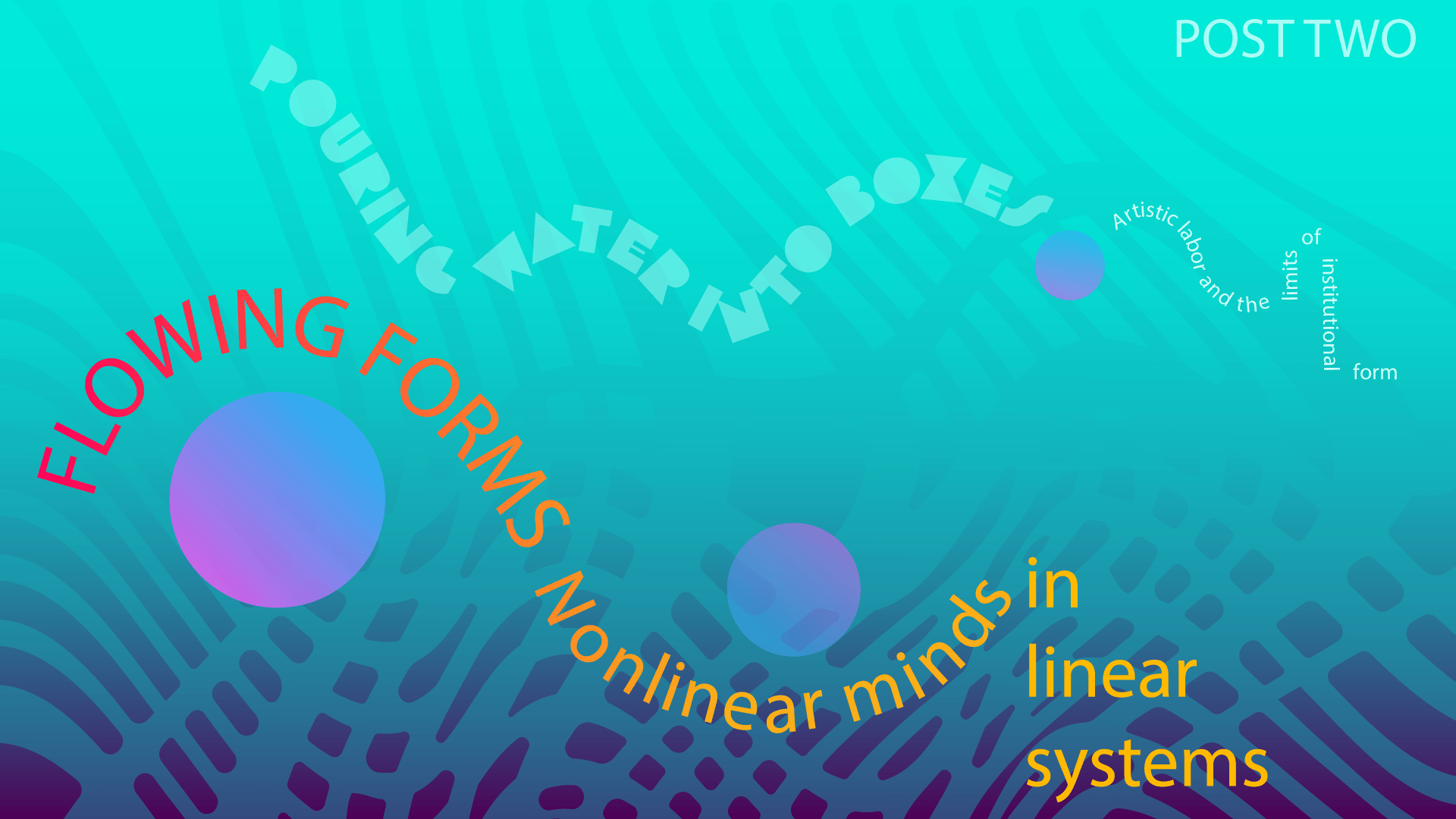

Flowing Forms: Nonlinear minds in linear systems

In my last post, I examined how arts opportunities often pair expansive civic ambition with narrow material support. This piece looks more closely at application formats for arts funding and other forms of support, and their reliance on linguistic fluency, narrative coherence, and clean categorization.

For the past fifteen years, a large part of my work has involved listening to artists, asking questions, and translating their responses into words so they can make the case for material support. I sit with people who perceive their projects as an interconnected, flowing whole. They sense relationships, momentum, aesthetic logic, and emotional charge all at once. The work is alive for them long before it can be named. What they often struggle to do is turn that three-dimensional flow into a linear sequence that a reader can follow in a grant application or a pitch to a presenter.

This is the guidance I find myself repeatedly giving: even if you can see the house all at once, you still have to walk the reader through it. You have to decide where the tour begins, what comes next, what needs to be named explicitly, and what can remain implicit. You have to narrow your frame of view and move it step by step, narrating the entire time.

For many artists, this feels foreign—even intrusive. Much artistic work emerges from nonverbal realms of consciousness. Decisions are made through sensation, rhythm, spatial awareness, affect, intuition, and embodied memory long before they are available as language. Over and over again, I watch my clients struggle as their generative artistic processes crash against the narrative demands of application systems that privilege verbal articulation as the primary evidence of thinking, planning, and visioning.

If fluent language were equivalent to thinking, large language models would already be intelligent in the way humans are. They aren’t—because intelligence is embodied, situated, temporal, and relational.

In reality, many forms of complex ideation occur entirely outside of words. Artists, athletes, engineers, and designers routinely think through movement, spatial reasoning, pattern recognition, pressure, timing, and embodied feedback long before ideas are verbalized. Entire domains of human knowledge operate at this level.

Fields such as engineering and design rely heavily on prototypes, models, simulations, and iterative testing rather than requiring full verbal articulation in advance. In sports, capacity is evaluated in motion through action, feedback, and results under real conditions. Athletes are not required to fully explain their potential performance before they are invited to join a team.

The arts funding context in the United States, however, remains a place where the bias favoring language is especially visible. Here, legitimacy, readiness, and merit are still overwhelmingly determined by an artist’s ability to translate nonverbal, emergent thinking into language-heavy formats at early stages of project or organizational development.

In artistic practice, form and function co-arise through flow, over time and in context. What the work is and what it does emerge together through making, rather than being fixed in advance. Institutional systems tend to reverse this logic. They require declared function and stable form upfront, as a condition for allowing flow to occur at all.

In application narratives, artists are asked to describe outcomes, impacts, and trajectories before the work exists. They are asked to stabilize ideas that are still in motion, to forecast effects that depend on context, and to present certainty where experimentation is the point.

Systems that privilege linguistic fluency, narrative coherence, and clean categorization reward those who can perform those skills, regardless of whether they reflect the intelligence actually driving the work. Artists often notice this themselves, remarking that certain colleagues are “good at getting grants,” even when the work itself feels thin.

As an intermediary, I’m glad when artists gain the skills to navigate these formats more effectively. But it’s worth naming where the burden still falls. The work of translation, of reshaping nonlinear thinking to fit linear forms, is disproportionately carried by those with the least institutional support. The self-education required to meet these demands often has little to do with artists’ actual practices as choreographers, sculptors, and other makers.

Long before I was working in grant and institutional contexts, I was already exploring this tension in my own artistic practice. Years ago, I conceived and led a series of dance technique classes called Flowing into Form. The work focused on cultivating flow as a way of entering technical forms, allowing those forms to become dimensional—alive with depth, pleasure, richness, and presence.

One of the central insights of that work was simple but unsettling: just because a human body is moving does not mean it is embodied. When dancers move primarily through forms designed to fulfill hegemonic cultural values—without regard for the individual intelligence, sensation, and perception that animate them—those forms can distance dancers from their own embodiment. Pouring flow into a static container preserves the container, not the flow. What remains is form without the full, generative presence of the human inhabiting it.

The issue here is not whether artists should be able to communicate or plan. It is that when institutions claim to value experimentation, nonlinearity, and complexity, but require linear certainty at the point of entry, those values remain rhetorical. The forms we design shape who can enter, what kinds of intelligence are recognized, and what kinds of work are privileged.

Again, I’m not offering solutions here. I’m trying to describe the structures many of us are moving through and the kinds of intelligence they tend to reward. Seeing this clearly is a necessary first step before new models can emerge.

#pouringwaterintoboxes